(Article for ‘Roma Gadga Dialog Initiative’, to help raise standards of education for Gypsies in Slovakia. By Simon Bird, Roman Pecha & Alex Brigers.)

After a two hour walk from the campsite, I finally emerge from the vast forest of Slovinsky Raj (‘Slovak Paradise’) National Park. Before me lies a dishevelled village of log cabins and muddy paths. I can hear people shouting; a smell of burning wood fills the air and I am overwhelmed by feelings of excitement, and to some degree trepidation.

The settlement is Letanovce Roma Osada – a ‘Gypsy village’!

Exactly two years ago I had all my food stolen here by a few Gypsy youths. I had offered them some rolls and salami, but, as soon as I opened my bag their hands darted in and took everything.

In that summer of 2006 I spent three weeks making paintings of Gypsy settlements. I found, by painting on location in the villages, I could meet the people and learn more about their situation in Europe today.

Some of the settlements I visited had no electricity, running water or sanitation. One village in particular stuck in my mind from that summer – Letanovce Roma Osada.

It seemed like a village from the Middle Ages: log cabins falling apart; screaming children walking barefoot in the mud. I felt like a time traveller.

Ten years ago the Government promised them a new village, but nothing has materialised.

- Amnesty International report, Nov 2007: The Gypsies of Eastern Slovakia are among the most deprived communities in Europe. Many live in settlements or neighbourhoods that are physically isolated from other parts of the community, with limited or no basic services.

- Slovakian Government Census, 2004: Gypsies in Slovakia make up 4 to 6 per cent of the population; roughly 500,000. Of these 25 per cent live segregated from the rest of the population.

History of the European Gypsies.

Through the study of linguistics it is believed Gypsies originated, not from Egypt, but from the states of Punjab and Rajasthan in North-West India.

They started to leave India as early as the 3rd century AD, escaping from invading Islamic forces. The first written records of Gypsies in Slovakia are during the 15th century, but it is suspected they would have arrived a few hundred years before that.

To begin with, they were met with a degree of hostility by the Europeans. Through time, they became more tolerated, but not fully accepted into society.

In 1958, the Czechoslovakian Government outlawed the ‘Nomadic lifestyle’ led by the Gypsies. Although the State supplied some housing it was not enough, so many Gypsies were forced to settle on farmland. After the fall of Communism in 1989, landowners started to claim back property that was once theirs. This has led many Gypsy settlements to exist on private land.

In 1958, the Czechoslovakian Government outlawed the ‘Nomadic lifestyle’ led by the Gypsies. Although the State supplied some housing it was not enough, so many Gypsies were forced to settle on farmland. After the fall of Communism in 1989, landowners started to claim back property that was once theirs. This has led many Gypsy settlements to exist on private land.

This is exactly the story of Letanovce Roma Osada. The village exists on private land, so the Government does not want to supply services to them, like electricity or water. Instead, the Government has said it will build a new village for them 10km away. This initiative was started 12 years ago, but is still in process.

Three distinct Gypsy groups exist in Slovakia: ‘Ungrike Roma‘ from Hungarian, ‘Vlachika Roma’ from Romania and Moldova and Slovak Roma ‘Servika Roma‘, being the least integrated and most isolated from society today. All the Gypsy settlements I visited have been of Slovak Roma.

Return to Letanovce Roma Osada 2008.

I enter the village carefully; the ground is muddy, and the rain is starting again. The log cabins look in exactly the same state of disrepair as before – the only difference being that a few more had been painted carnival pink and light blue.

A crowd of people form around me as I make my way through the village. A few recognise me; one kid even remembers my name, Simon Ptak ‘Bird’, because the translation has rude connotations in the Slovak language.

The rain becomes heavy and I am invited into a house by a young man pushing a wheelbarrow of firewood. His name is Palong, a young, sharp-faced gypsy with slanting eyes and strong cheek bones. I had not met him on my previous visit, so I thought he would offer me a fresh look at the situation here in Letanovce Roma Osada.

Palong’s house is a simple 15 by 15 foot log cabin with two windows. Inside, walls and ceiling had been plastered and painted pink magnolia. Two large beds double as seats; a chest of drawers acts as a kitchen work surface; and, the log burner heats the room and is used to cook the food.

Palong lives with his parents, a few sisters, his wife, and their baby. Everybody has rosy cheeks and deep-set eyes and scrutinize me intensely. Although, they are probably more worried about what I think of them, rather than me being any threat. They smile, and make me a Tureka coffee: a coarse ground coffee steeped in a mug of hot water.

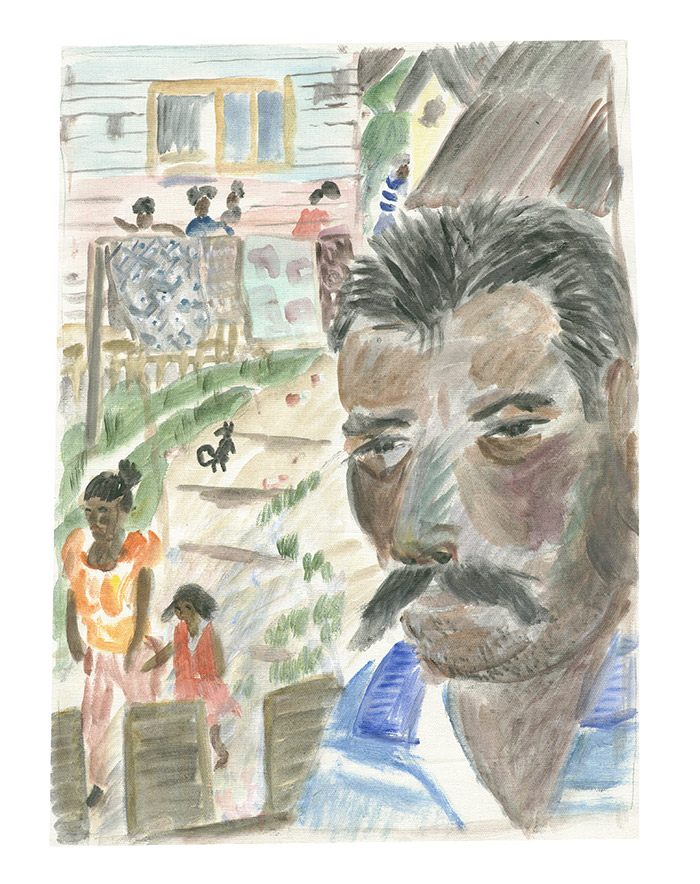

( This is Palong standing in front of his family house that sleeps 6 people. The trees that made this log cabin were felled by axe and dragged by hand to the village.)

I am also offered mushroom halusskew (goulash) by Palong’s mother, a handsome lady wearing several head scarves and silver loop earrings. The halusskew consists of dried mushrooms from the forest, with handmade pasta squashed into small lumps with thumb and forefinger. It is quite sour and salty, but delicious. This dish is a speciality during the cold winter months when temperatures drop to -20 degrees Celsius and there is 10 inches of snow outside.

Palong’s father turns on a black and white TV, powered by a car battery. He is a quiet old man with dark ragged skin, which makes me think that his ancestors came from the Himalayas.

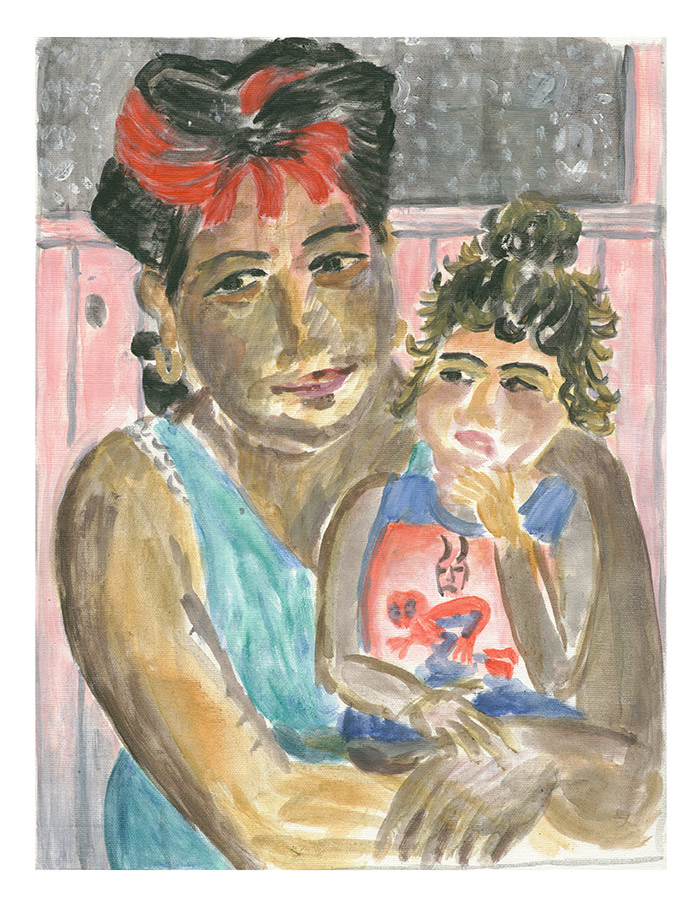

Palong and his wife have been married 4 years, an arranged marriage, but Palong says he fell in love at the same time. They are very proud of their newborn baby, which his wife plucks from under some bedclothes and thrusts in my face. “Gadga, Gadga,” she says. ‘Gadga’ being a slang word for White European.

I ask Palong about the new village promised by the Government. He says that the houses are nearly finished and that the Government will move them in 2009.

After the rain stops, I go with Palong to take some photographs of all his friends and relatives. I arrange to return the following day, so we can go to Spisska Nova Ves to develop them.

I bid farewell, and, as usual, the kids from the village chase after me excitedly.

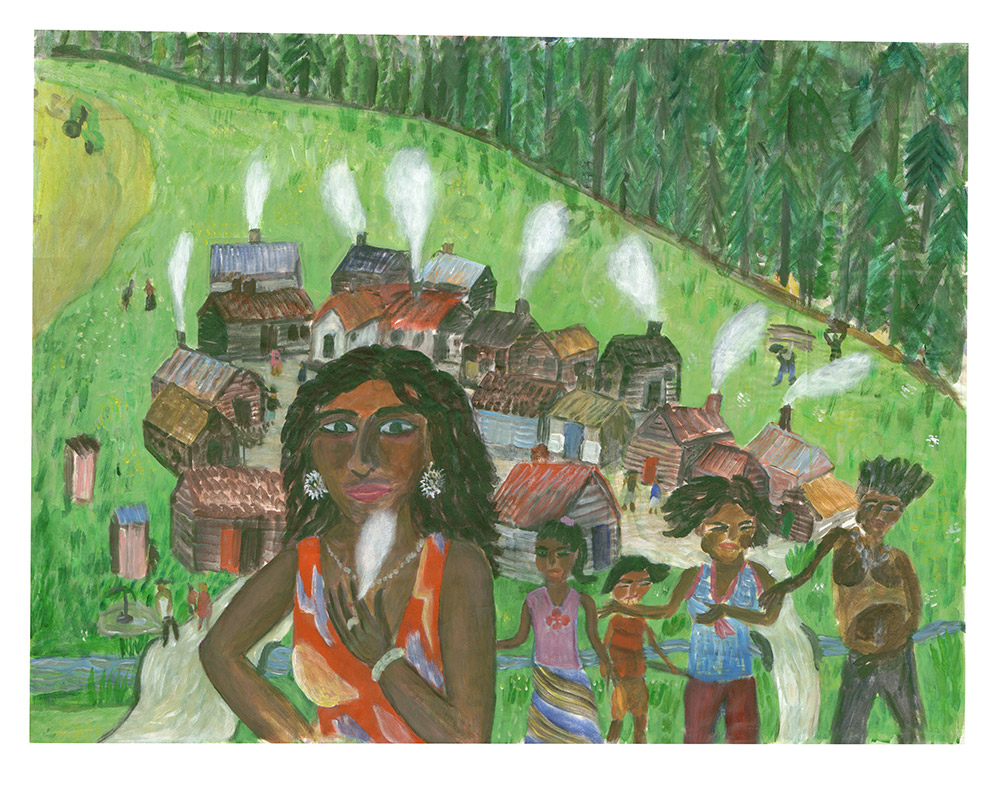

Painting in Letanovce Roma Osada 2006

Letanovce Roma Osada was the first village I came to back in 2006. In retrospect, I should have spoken to the village chief before starting to paint, but I went straight out and positioned myself on the road that leads up to the village.

As I sketched in the assortment of dishevelled houses against the backdrop of the magnificent forest of Slovinsky Raj, I was reminded of how I believed life could be in the Middle Ages, and, yet, considering how modern the rest of Europe has become, I could not comprehend how these people, who live within its own backyard, have been so neglected.

I let some kids colour in the picture. They worked freely; they had used paints before at school. I noted that it was important for them to make the houses look as good as possible.

Several parties of men passed on their way back from the shop in the nearby ‘white’ Slovakian village of Letanovce. One man was pushing a pram. Inside, instead of a baby, I found a sack of potatoes and a few empty beer bottles. He kindly hung around to control some of the kids, who were throwing grass around, but, after 15 minutes, he wanted to be paid for his services.

When a few kids ran off with my painting pallets, I had to call it a day. They did return with them, eventually.

My first day’s painting had been exhausting, but exhilarating. As I walked back to my tent, I felt like I had discovered a lost tribe in the middle of Europe.

( A girl’s painting of her Babichka ‘Grandmother’. It is still common in Gypsy villages to find 3 generations living together under one roof.)

( A boy’s painting of his home in Letanovce Roma Osada. Conifer trees stand either side of the house; he says he has to go to the forest everyday to collect fire wood for heating and cooking.)

Going to Spisska Nova Ves.

The next day, I meet up with Palong as planned. He is pleased to see me, and I get the impression that he thought I would not be turning up. We have a Tureka coffee with lots of sediment, and walk the 2km pot-holed road to the railway station.

It is three stops to Spisska Nova Ves, the largest town in the district. You rarely see ‘whites’ hanging out with Gypsies in Slovakia, so I felt a bit self-conscious sitting on the train next to my new friend. Just before we arrive at Spisska Nova Ves, the train passes another Gypsy village – Smizany Roma Osada – I had visited back in 2006.

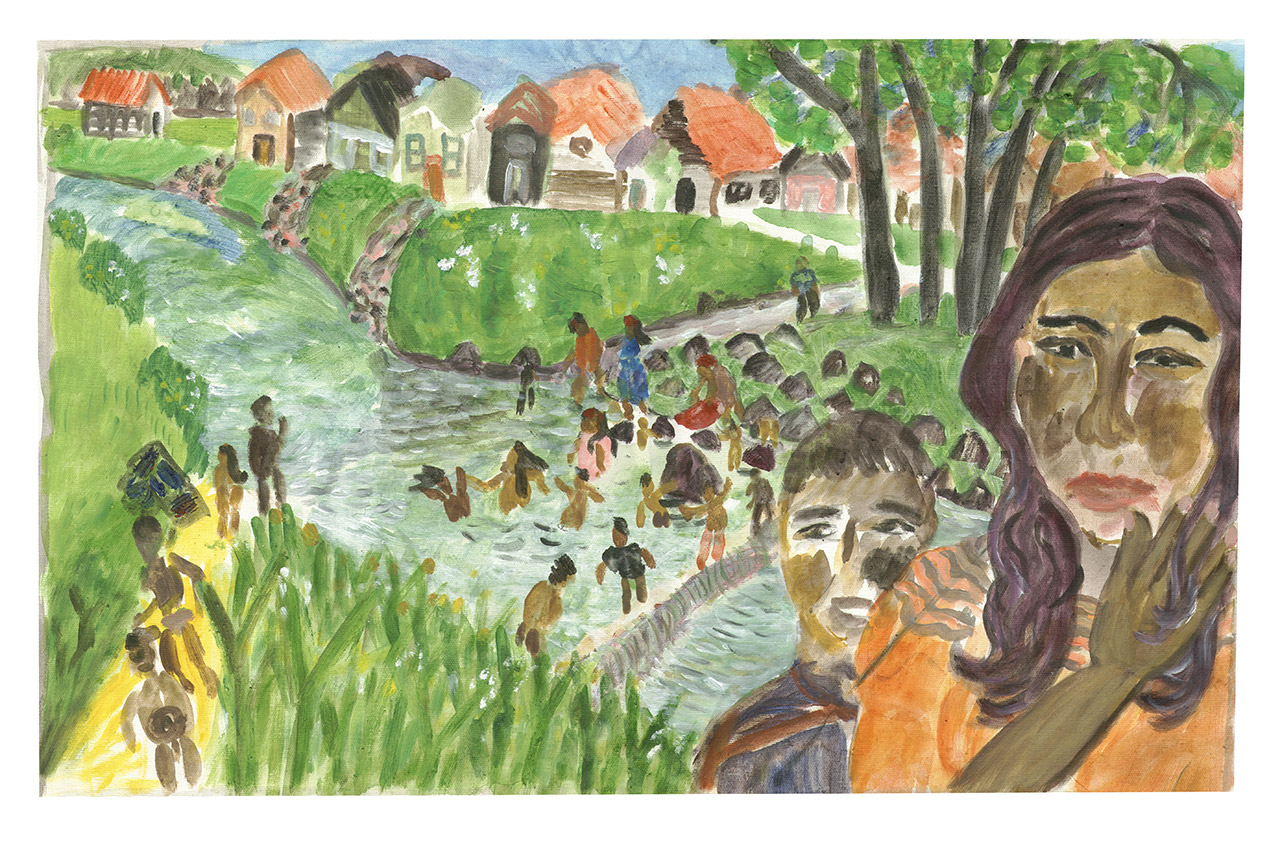

Painting in Smizany Roma Osada 2006.

Smizany has a reputation for being a rough place, but walking through the village the atmosphere was quite relaxed, and people were sitting outside their homes chatting amiably. It was a stupendously hot day.

The best place to do a painting was from the bridge overlooking the river. A dozen or so people were cooling off in the water; women fully clothed like in India. The only worrying factor was that the local rubbish dumps were slipping into the river further upstream.

My spectators were alternating between viewing my painting and jumping in the river. I asked one Gypsy man, who had a factory job in Spisska Nova Ves, what they prefer to be called. I had heard several names used: Gypsies, Roma or Cikani. He says that Cikani is the Slovakian name, Roma is the official name from Gypsy language, and Gypsy is from the English language. I decided it was all right to continue to call them Gypsies, being English myself.

Spisska Nova Ves

Palong taps my shoulder; we have arrived at Spisska Nova Ves railway station.

We find a shop to develop the photographs on the edge of town; Palong would have to return in two days to pick them up. Next, we go to the supermarket to buy lunch and a few beers. But, my new companion breaks the top off his beer bottle trying to open it on a ledge, and refuses to drink it.

On the way back, we get off the train at Spisska Thomasovce village, I want to introduce Palong to a Gypsy friend of mine, who speaks good English.

However, there is a problem. Palong does not want to enter the house. “They are a different kind of Gypsy. I will get beaten up,” he protests.

Finally, with a lot of persuasion from my friend Roman Pecha, he goes inside. The interior of my friend’s house is a normal Slovakian home, a world apart from Letanovce Roma Osada.

Roman Pecha was a Teacher’s Assistant in an all Gypsy school in Letanovce, and is now coordinating a teacher exchange programme for ‘Roma Gadga Dialog Initiative’, to help raise standards of education for Gypsies in Slovakia.

The interview

I wanted to know what had happened to Palong’s schooling, and ask some questions about his views of ‘White’ Europeans.

Palong had said he went to school from the age of 7 until 16, but cannot read or write. I ask what happened.

“It is my fault. I learnt something, but only a little of mathematics and Slovak language,” Palong says.

“Was there a problem with the teachers?”

“It is my fault,” he repeats.

I ask if he will send his daughter to school to get an education.

“Yes.”

“He has to”, says Roman. “But it will never happen, Simon, that’s my opinion.”

Next, I ask Palong about his view of ‘white’ people.

After a long pause, Palong answers. “I think nothing about the Gadga.”

Roman says:” Obviously, he is scared to say anything else.” He turns to Palong. “Do you really think so, Palong. Slovakians say the dead Gypsy is a good Gypsy.”

“Yes, you are right, that’s true,” concedes Palong.

“What have you been told about moving to your new village?” I ask.

“The Government said they will move us in 2009. I will share a house with my parents.”

I ask Roman why Palong did not want to enter the house.

”It is because he feels lower. He has said this to me.”

“Why does he feel lower?”

No answer.

I try a different tack. “Is Letanovce Roma Osada the lowest class of Gypsy in this area?”

Palong quickly answers: “Not the lowest. In Rodune… those people eat dogs.”

“Did you ever steal from tourists when you were young?”

“Never.”

“Do you know people that did?”

“Yes, many.”

“Do Gypsies steal from each other?”

“No, I have never seen this.”

“So, they don’t steal from one another.“

“Oh, they do steal,” Roman interjects.” I don’t agree with him.”

“So, is there a problem with stealing in Letanovce Roma Osada?”

After a pause, Palong agrees.

During the interview it became obvious to me that Palong was genuinely afraid to answer some of the questions. If this is a fear shared by other Gypsies in Slovakia, it means more dialog should be created between the ‘Gadga’ and the Gypsy, for society to improve.

Segregation of Gypsies in Education

Roman Pecha explains that segregation in the education system starts in two ways. The first is that children are segregated into Roma-only classes. The second is that children are inappropriately placed in ‘special schools’ for physical and mental disabilities. Today 80 per cent of children placed in special schools are Roma.

Amnesty International argues that integration is the key tool for building understanding. However, the contact between Roma and the rest of the population in Slovakia is minimal, and often non-existent.

The new village for Letanovce Roma Osada

The next day, I go to see the new village for Letanovce Roma Osada, built by the Government.

The walk takes me from Spissky Stvertok to Hrabusice, roughly 7 km. Halfway, I see the new village surrounded by fields of yellow rapeseed. The houses look like agricultural sheds in neat rows.

The main problem that strikes me, however, is that the location is again isolated from the ‘white’ population.

I was informed by a Government worker that, although the houses are finished, the village and the future occupants have yet to be registered with a local council. The neighbouring villages of Spisski Stvertok and Hrabusice have refused to have the Gypsies registered with them, because they do not want the Gypsy children going to their schools.

The solution looks set to be that the Gypsies of Letanovce Roma Osada will stay registered with the ‘white’ Slovakian village of Letanovce. The only problem, is, that, a new road will have to be built connecting the two villages, which means, the Gypsies who have already waited 12 years for a new village will have to wait a few more.

Hrabusice

As I stroll in to Hrabusice, a tidy village with lots of B&Bs, I bump into ‘Simone’ a Gypsy beauty with long curly hair, whom I met back in 2006. She had told me, half-jokingly, that she was from ‘Beach Mauritius’. Her family had made money, and did not want to be associated with the poorer Gypsies that live up on the hill.

The Gypsy quarter in Hrabusice occupies the hillside above the village. Since I was here last, a row of new bungalows had appeared. They were the same colour and description as those I had just seen at the new Letanovce Village.

On the way up the hill, I shake hands with a few Gypsy elders, who look just as inebriated as I had seen them, two years before.

At the top, Johnny, a young man, recognises me. “This is America!” he yells.

I look across at the view over the village to Slovinsky Raj National Park. It was, indeed, a dream, by far the best view in town.

The new bungalows are carpeted and are equipped with all the usual mod-cons associated with the rest of modern Europe; but, there again, Hrabusice was never like Letanovce Roma Osada. Their houses, also, had electricity, and many were supplied with running water.

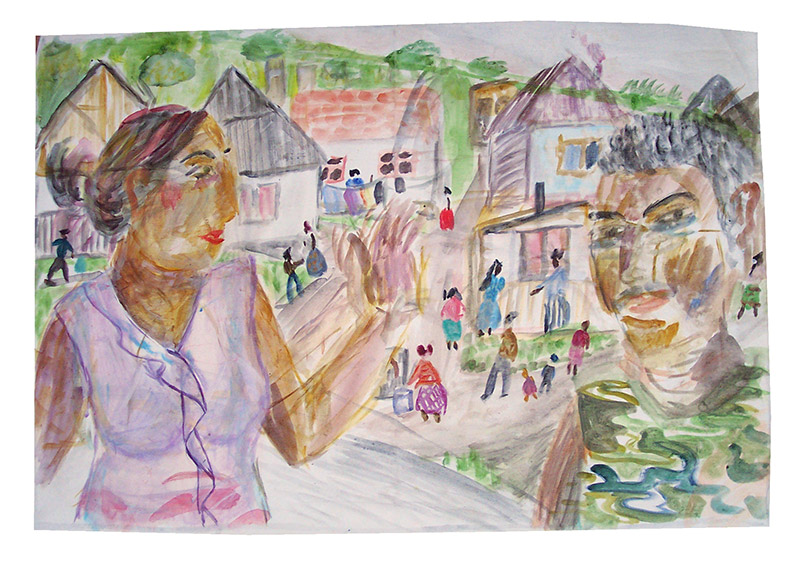

Painting in Hrabusice 2006.

(Painting of Hrabusice. The woman (left) was demonstrating a type of Gypsy dance in the street.)

I had one of my best painting experiences here at Hrabusice. Many people did there own pictures, and we had a lot of fun. Although, at one point, a car had lost control while reversing down the hill and ran over one of the pictures, and, as a consequence, I was blamed for nearly injuring someone.

(After the car ran over my painting, one Gypsy teenager drew a car for me as a memento.)

(An imaginative youngster pictured himself floating over his house in Hrabusice.)

Chat with Coffee Shop owner.

Sadly, it is time for me to leave. On the way to Spisska Nova Ves, I bump into Palong one last time. He is outside the post office with a large crowd of other Gypsies. They are waiting to collect their monthly benefit from the Government.

Palong tells me he is going to pick up the photographs today. I wish him and his wife all the best, and bid farewell.

Before catching the bus back to Prague, I get talking to a coffee shop owner.

“Cikany, means thief”, says the wife of the coffee shop owner.

They had spent six years in the US, and had returned to open this coffee shop with their savings.

“You can tell when the Gypsies get their money from the Government, because they blow it straight away in the outdoor cafes on the high street. Later today a woman will come along with a big broom, because it will be like a pigsty.”

“Maybe 5 per cent of Gypsies are like us, but inside they are still Gypsies,” says the husband, tapping his head. ” You only have to say something small against them, and they make it a big issue. They need to be educated, and they must integrate more with us.”

Epilogue: Gypsy origins.

Earlier in the year 2008, I am lucky enough to be passing through India, and so I make an effort to see the Gypsies’ long lost relatives in the North-West of India. I head to the holy town of Pushkar in Rajasthan, which is also popular with tourists, to search for the lower caste of the nomadic tribes. It does not take me long before I hear some music, with the familiar Gypsy rhythm, coming from the ghats outside a big hotel.

( The three Kabalayer girls I spoke to in Pushkar, Rajasthan.)

“I am not a Gypsy, I am Bopa musician,” says the lady who was singing. “Kabalayer are Gypsy; they are dancers, and paint henna on your hands.”

One of the Bopa kids runs off to find the Kabalayer. In the meantime, they enchant me with their hypnotic rhythm and chanting.

I discover that these two groups of nomads often work together entertaining the tourists, and that business here in Pushkar is good, because there are a steady supply of tourists.

In my beguiled state, I see three girls approaching me in long, colourful tribal dresses. Their lips are painted black, and their eyes are shaded dark purple. They float down before me with no sign of timidness. One of the girls takes my palm, and begins a henna design.

“Did you know there are people like to you in Europe?” I ask.

“Yes, I know,” one of the girls replies. It turns out she teaches Gypsy dance to backpackers, and so could speak a little English.

I ask what life is like here.

“Sometimes problem Kabalayer, sometimes no problem Kabalayer. I do not go to school. I learn English just from the tourists.”

For a small fee, I am invited into the desert to see where they live. About 2km from town on less than clean sand dunes are several camps of Kabalayer and Bopa. The odd goat is tied up and a few families own motor bikes. Their sleeping quarters consist of a sheet of plastic stretched over sticks stuck in the sand. Underneath are a few blankets that act as a bed.

Tea is boiled for me on an open fire. I sip the sweet brew, and watch the sun go down over the Thar Desert. The girls have their chores, like milking the goat and organising the youngsters.

For me, however, I was two thousand miles away, thinking about how the ancient Gypsies managed to travel across continents, and still preserve something of their original identity. The nomadic tribes of Rajasthan are among some of the most decorative in the world. Their dance and costumes have inspired nations. It seems unbelievable to me, considering that with such rich heritage from their ancestors, the European Gypsy has not been more respected or accepted over the years.

Article for ‘Roma Gadga Dialog Initiative’, to help raise standards of education for Gypsies in Slovakia. Co-ordinator Roman Pecha. By Simon Bird & Alex Brigers. November 2008.