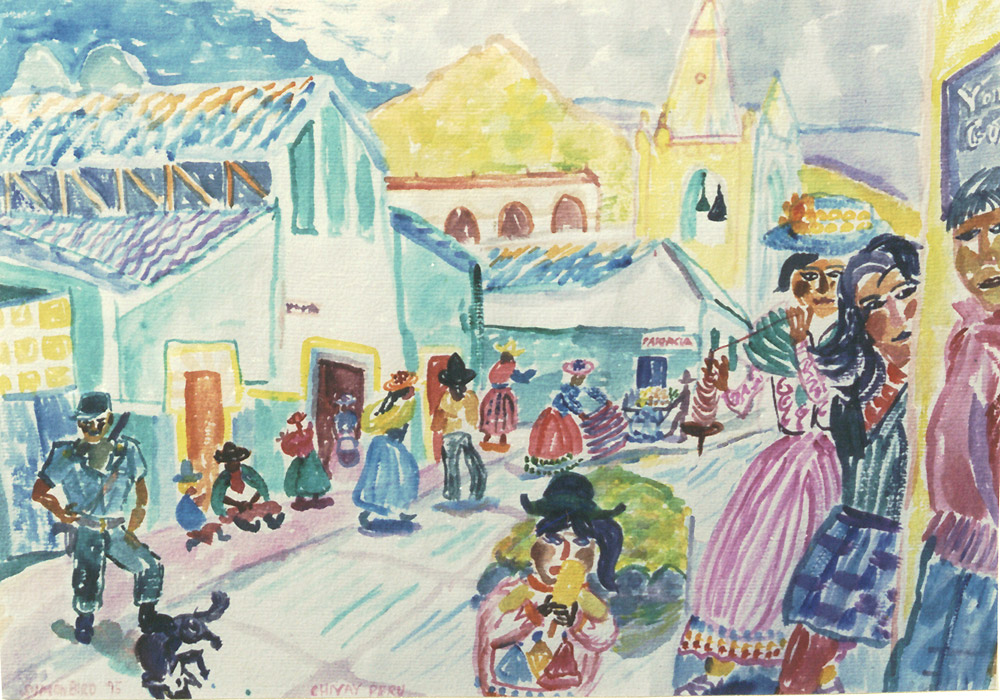

I made a point of sketching directly in the street with watercolour to capture the eccentricities of everyday life. The indigenous Quechua and Aymara Indians were always interested in what I was doing. Some wanted to help me paint, other would just say what I should paint!

An annoying dog kept running over my picture, so this policeman came over and put his foot on the dog to control it. He was very proud at exercising this duty, and insisted that my picture will be exhibit it in the town hall.

He ordered passers-by to stand still while I sketched them. He said my art work took precedence over catching bandits!

“Are you paid by your government to do this ?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“I work for my government, but would like to learn to paint like you,” he said.

To me he seemed a very unlikely character to want to paint in watercolour, as several times he’d mimed letting his gun off at the poor dogs head.

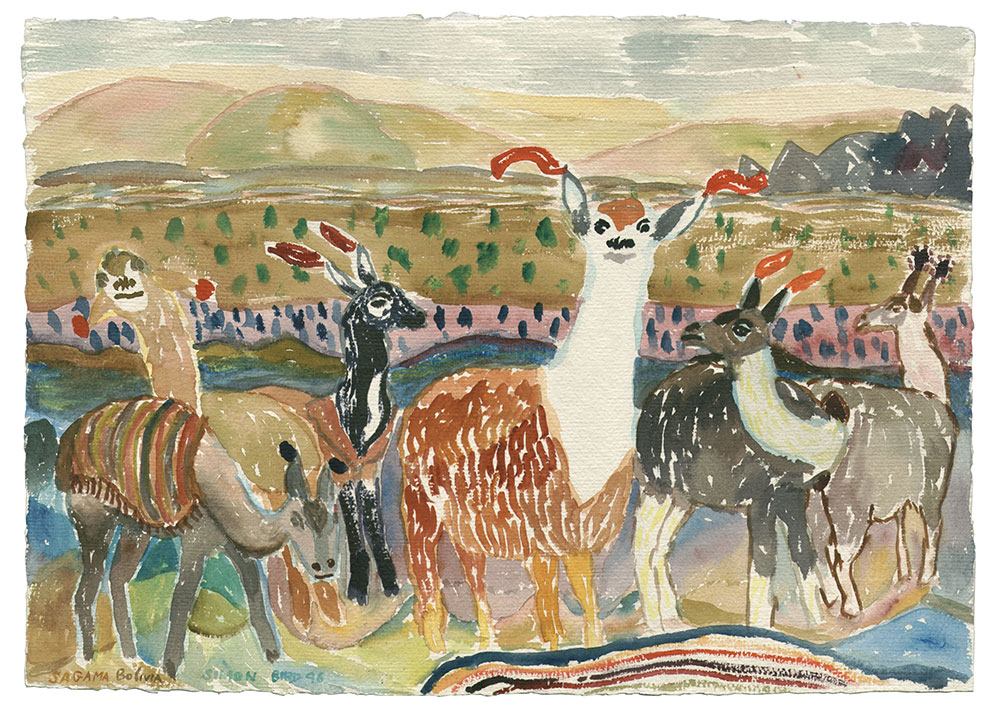

Admiring the picture the father of the family warned me not to go hiking too far around these mountains.

“There are no bandits,” he said, “but it is very dry.”

He showed me how they have to channel water from a stream some miles away.

“Last year a German tourist walking over towards the volcano and didn’t come back,” the father explains. “He got dried out!”

“I was the one who found his remains.”

Cero Rico (Rich Mountain), Potosi.

Since the first Spanish conquistadors arrived in the region, this mountain has been mined for Silver. Local Indian slaves and prisoners were employed to do most of the digging – many died. Now, 300 years on, much of the inside of the mountain slides down the outside, which makes for a slightly surreal and poignant back drop.

A picture by local kids with football and Cero Rico in background.

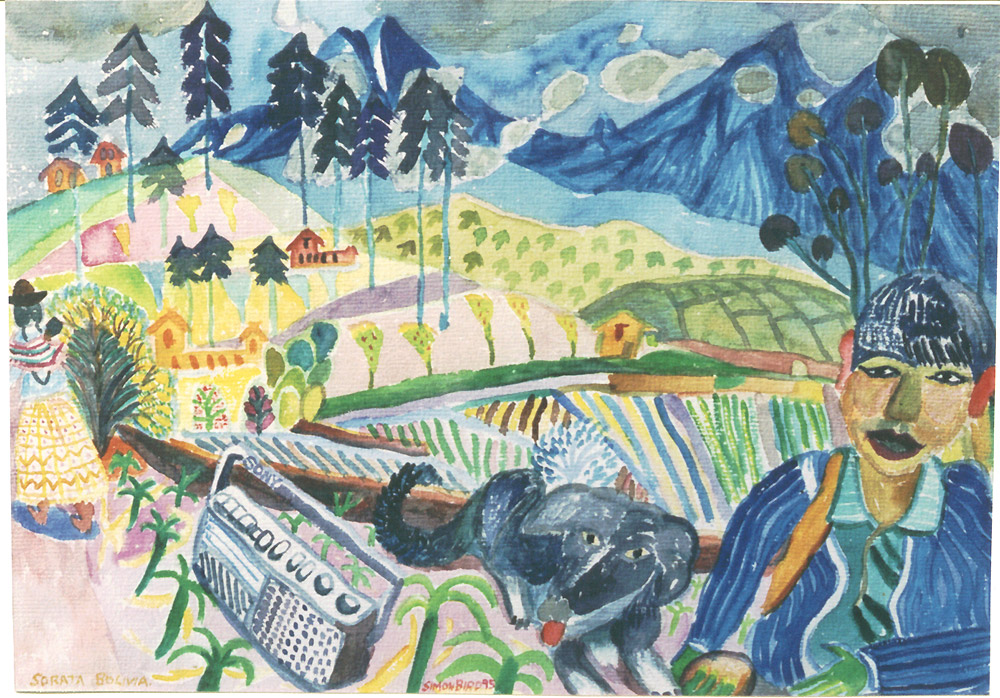

I found this spot high up from Sorata town. This boy sat with his dog and turned on his radio.

He told me he was on his way to school, but he ended up staying most of the day. When I finished the picture he disappeared back the way he came.

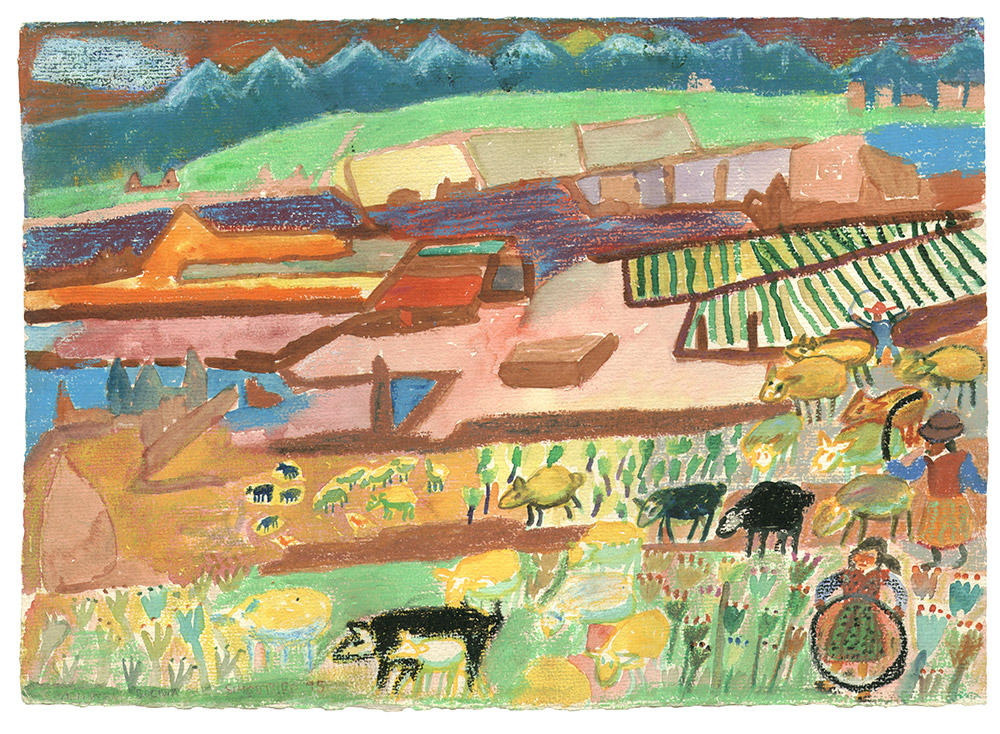

These herders helped colour in the picture and added the mountains at the top when there wasn’t any mountains.

“I can’t see any mountains!” I said.

They assured me, however, that they were there, but just beyond where you could see.

In the end, I gathered a picture of Bolivia without the mountains, was like a shepherd without his sheep. The fact you could not see them didn’t matter, they are a symbol of there homeland.

Two days by bus, then a further two days walking to reach Sajama National Park, altitude 4200m. I survived on llama stew and alpaca steak – kindly dished-out by the villagers!

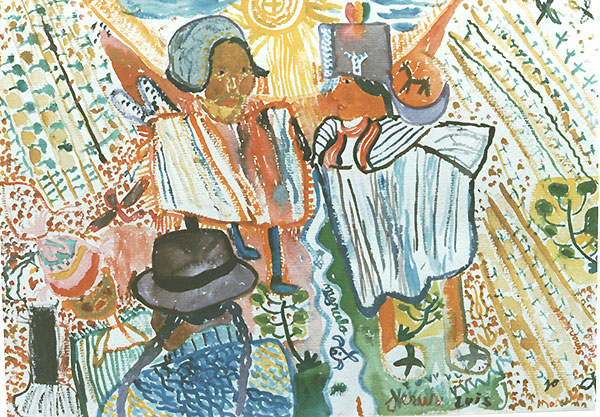

Tiabuku market, Bolivia.

Here in Tiabuku the locals wear skullcaps, echoing the style of helmet the first Spanish conquistadors had. The square topped hat is for women after marriage.

The local market sellers who helped to paint this picture have also signed their names. They told me for a perfect image of Bolivia the sun should be sending its rays out over the people and rows upon rows of potato plants.

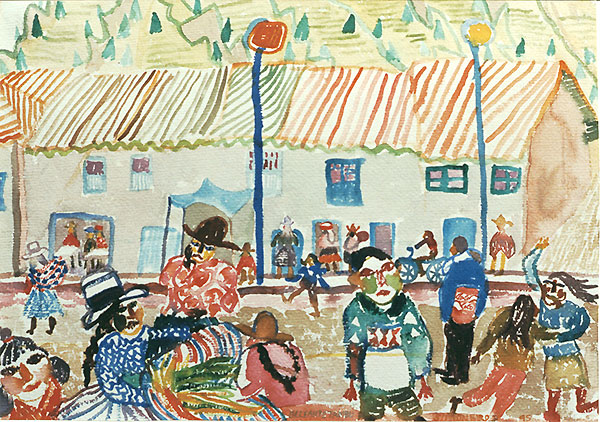

I had a fever, but was bored of lying in bed. So, I took a couple of paracetamol and went out into the plaza to paint.

It was a small traditional market town, but where everyone looked a little strange and twisted!

After painting, I went back to bed and my flu worsened, and lasted for a further two weeks.